KODAKAN

Kodakan, verb – the generic Pilipino term for taking photos derived from the known camera brand Kodak.

Example: “Kodakan na! It’s picturing taking time!” Synonym: “piktyur piktyur” or “piktyuran na”

What does it mean to be Pilipino in San Francisco? And how do we tell our stories by posing for the camera?

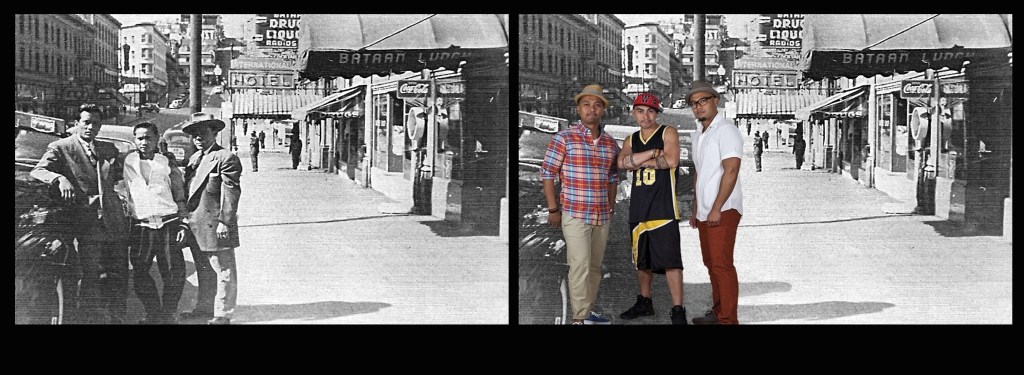

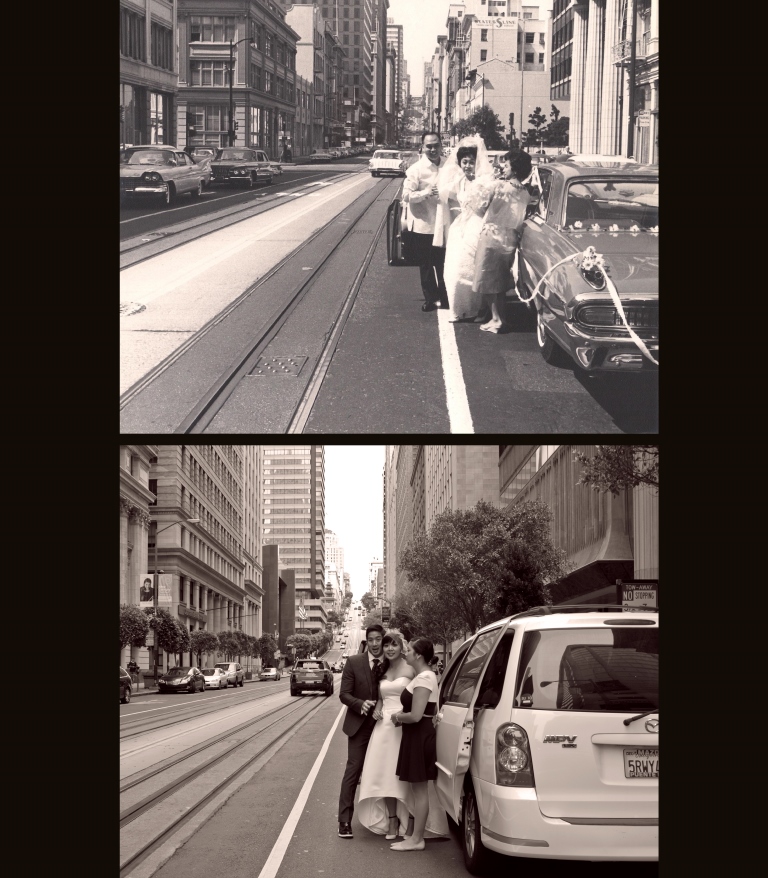

Presented by Kularts in partnership with the Filipino American Center at the San Francisco Public Library, Kodakan: Pilipinos in the City explores changing expressions of Pilipino cultural identity through the simple act of snapshot photography. Inspired by images in the book Filipinos in San Francisco and the San Francisco Historical Photograph Collection, lead artist Wilfred Galila with Peggy Peralta and Cece Carpio, create playful photo homages to the vintage photos. Accompanied by videos, poetry, and interview snippets, the artists share the varied faces and stories of the San Francisco Pilipino American community.

Statement from Alleluia Panis, Executive and Artistic Director of Kularts

The Pilipino American experience is as diverse as the Philippines 7,100 islands and 180 ethnic groups. The boundaries of the Philippine nation were drawn, not along indigenous tribal lines, but in the service of a European power. After 400 years of colonization by Spain, and then 50 years of occupation by the United States, our identity has been obscured, not only from others but also from ourselves. Pilipinos continue to be simultaneously visible and invisible—even though Pilipinos have lived in San Francisco since the late 1800’s, and the Bay Area Pilipino population numbers over 460,000. Kularts developed our Making Visible initiative to address this concern, and we are proud to see the realization of this project with the Kodakan exhibition. We hope that the personal narratives contained in this exhibit illuminate our past as well as our present.

Piktyur-piktyur

Every Pinoy knows the end-of-event photo ritual for family or community gatherings. Someone calls out, ‘picture picture!’ or ‘piktyuran,’ then all attendees stand in a row—or several rows. No matter how large the group, no matter how much time it takes, everyone must be in the picture. These recorded images serve as a kind of photo diary where, we, the subjects are in control of how we want to be remembered or recorded.

Culled from private family albums, many of the photographs in the 2011 Filipinos in San Francisco book were of this sort, folks lined up after an event or in front of a building or park. It is as though the photos are evidence of something, even if only to ourselves—evidence that we matter, that we were there—wherever ‘there’ is. What strikes me, while leafing through the book, is that the photo subjects, not the photographer, are the architects of their own image, performing for the camera. Perhaps, more poignantly, these early office workers, waiters, seamstress, and farmworkers were projecting their American dream of ease and wealth onto these photographs. In these pictures, they can dress in impeccable suits/dresses and pose leisurely. Couples sat together in muted bliss on park benches or stand at famous tourist destinations, as though they have all the time in the world. Young families and friends proudly shed their provincial upbringing in the streets of a modern San Francisco, far from the rural villages, barrios, and towns of the Philippines.

The Project

Embedded in these photographs are precious narratives relevant to us today. These questions guided the creative process: Who are the Pilipinos of today? What are the commonalities and differences of Pilipinos in San Francisco then and today? Do the lives of Pilipino American today reflect the hopes and dreams of early immigrant Pilipinos? How do we honor those who came before us while revealing ourselves for the camera?

We hope the project will empower the community to investigate and celebrate its stories, past and present.

Mabuhay Tayong Lahat!

Alleluia Panis,Executive & Artistic Director